From Rapids To Rocks

Tales from Ontario's historic Route Champlain

"I am in such a happy place right now."

Claudia Van Wijk gently floats on the Ottawa River, at the end of a warm summer day in her corner of paradise.

As the owner of OWL Rafting and a champion paddler, Claudia has spent her whole life on this waterway. Known today as the Ottawa River, but 10,000 years ago it was the western arm of the Champlain Sea.

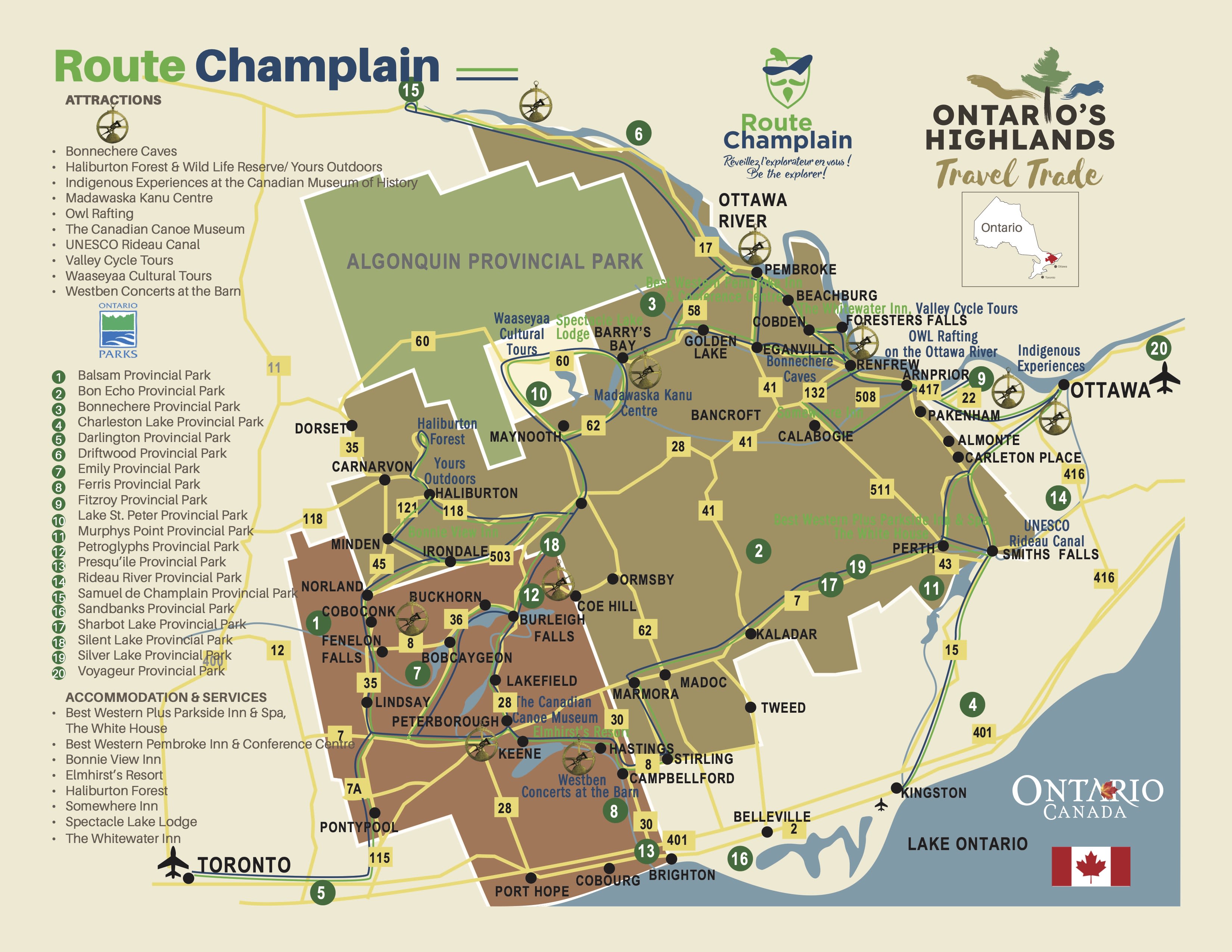

The surrounding landscape, anchored in heritage waterways and fascinating geology, is part of the historic Champlain Route, a 1,200 km scenic route that follows the path taken by French explorer Samuel de Champlain in the early 1600s.

The nature along the route is breathtaking and its history, steeped in Indigenous and French culture, is captivating.

Everywhere, fragments of untouched time allow us to put history into context.

"It's the Canadian Shield," says Claudia, explaining the region to me in the same manner she does to the paddlers who come to OWL Rafting.

"Two billion years ago, I think, the mountains here were higher than the Himalayas are today. Four glacial periods later, the last being 10,000 years ago, it has carved this granite down, and this part here was the Champlain Sea. All the way up to Algonquin Park was salt water."

The Ottawa River is a remnant of the Champlain Sea, named as such in 1906. At a maximum depth of 90 metres, it is deeper even than the mighty St. Lawrence River, into which it drains to the south. Where it flows into Lake Rocher Fendu, cliffs adorned with blueberry bushes rise about twelve metres high.

Human presence dates back at least two millennia. The river has been an important fishing site and a significant travel route for the Algonquins. Then, 400 years ago, Europeans began using it to transport furs.

“You know, 400 years ago, 50 Voyager canoes went by this same shoreline, every day,” Claudia says. “50 a day! Like, that's crazy.”

Over the past 200 years, the power of the river has been utilised by the forestry industry, and later for hydroelectric power generation. The Ottawa River and its tributaries host more than forty dams.

Lake Rocher Fendu is, in a way, the result of this. Its formation already existed, but the Chenaux dam, some 2 km downstream, flooded the shores and submerged some rapids.

"Even the locals here remember that right where we are now were some big rapids," says Claudia.

The rapids were strong enough for the First Peoples to prefer taking long and arduous portages. Champlain is said to have even lost his astrolabe there, which has become part of the regional lore.

Today, Claudia guides people through some of the rapids that Champlain and the First Peoples sought to avoid through the business her parents established and which she now entrusts to her daughters.

"400 years ago were the voyagers, 200 years ago was the ‘A’ point of the logging industry, and now we call it the rubber industry. Rubber rafts.”

Claudia Van Wijk: In her own words

About forty kilometres to the south, Chris Hinsperger provides a different type of experience, but also one shaped by the ancient Champlain Sea.

When the waters of the Champlain Sea receded, they left behind traces and carved tunnels that protected fossils. The majority of these fossils date back to the Ordovician period, around 440 million years ago – long before the appearance of fish or dinosaurs. These are now known as the Bonnechere Caves.

Chris, one of the co-owners of the Bonnechere Caves, guides visitors through the scenic tunnels – a journey that takes you back in time.

Chris Hinsperger: In his own words

"I'm not a geologist,” Chris clarifies. “I just absorb geology through osmosis...I ask questions so I learn a lot from the people I meet.”

He shows a map of the Bonnechere River drawn by surveyor Alexander Murray in 1853, which indicates the presence of underground channels. Following his tracks, loggers settled in the region. The cement structure of a sawmill, which ceased operations in 1908, is still visible.

"In the 1950s, when my friend Tom came to this property, he had an idea. Already in the States, people were developing tourism. People were opening up caves for tourism and Tom had this idea that, well, 'if I blocked off the water and created an entrance and put in lights and a boardwalk, maybe I could have a tourist attraction."

The caves opened to the public in 1955. Chris has spent more than 40 summers guiding people through the tunnels and is now the co-owner.

"It's the things that us locals take for granted that we do here every day that are very special for people who come visit us," he says.

As a child, Cindy Jamieson would sneak off on her bike without her parents' knowledge to tackle the rapids of the Ottawa River. Her whitewater kayaking took her around the world, but her heart eventually brought her back to the river of her childhood. She now resides in Beachburg, close to the banks of the Ottawa River, where she runs the lovely Whitewater Inn, organizes trips, and is a bike guide and storyteller.

Of Scottish origin, Cindy particularly loves stories from the lumberjack days.

The Scots, the Irish, and the French Canadians cut down trees during the day and enjoyed lively evenings. Cindy recounts the exploits of the log drives, the families that slowly formed a colony in the region, and their lively and spirited evenings.

"My grandfather used to say, 'Here if you shake a pine tree, fiddlers fall out.'"

Her tales include colourful characters with complex issues.

"Of course, they fought," she says. "But they fought against everyone, even among themselves," she adds, laughing.

Traces of their history remain throughout the region and Cindy thinks about them often as she traverses the trails – forest and river – of her region. As an avid cyclist, she devours trails like log drivers used to roll on the logs as they descended the river's torrent. In her eyes, these log drivers were even more fearless than the kayakers who now shoot the rapids.

Visitors to the Whilewater Inn are encouraged to explore the Ottawa Valley's many beautiful trails, including the local BORCA trails that offer a series of single-track bike, hike and run trails in the Beachburg area. Bike rentals are available at the Inn.

"I just like to get away from where all the people and cars can be," Cindy says.

All of this history is now woven together by the Champlain Route, carried by humans, entrepreneurs, and guides who shine with their authenticity and their attachment to the land. They tell the stories of the First Peoples, the Voyageurs, the surveyors, and the lumberjacks.

The Champlain Route offers a personal, deeply human experience that brings us back to our place on Earth. It guarantees inspiration and delivers a profound experience.

Andréanne Joly

Andréanne Joly loves to explore, delve into, and showcase the francophone culture of Ontario and its attractions. She has been doing so for 20 years and would continue to do it for another 100 years as the richness, beauty, and diversity of Ontario's destinations never cease to amaze her. As a journalist and writer, she regularly collaborates with NorddelOntario.ca, the Culinary Tourism Alliance, Francopresse.ca, the newspaper Le Voyageur, and others.

Embrace Canada with Landsby

Landsby creates unique and immersive experiences that not only provide travellers with purposeful and enriching trips but aim to positively impact the host communities.