Threads of Identity

Two Métis Designers Are Weaving Past Into Present

While our story is a contemporary one of fashion and social consciousness, it began nearly two hundred years ago in the great expansive territory of the Prairies, the heartland of the Métis...

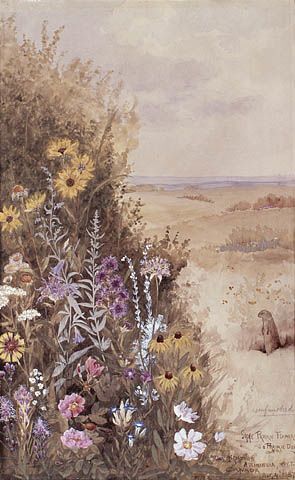

Prairie Flowers near Broadview, Assiniboia.Edward Roper, watercolour and gouache over pencil on laid wove paper, 1887. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1989-446-31.

Prairie Flowers near Broadview, Assiniboia.Edward Roper, watercolour and gouache over pencil on laid wove paper, 1887. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1989-446-31.

Lovely prairie anemones, white sagebrush, big bluestem and muhly grasses once bloomed along the riverbanks of what was then known as the Red River Settlement.

Inspired by these wildflowers, Métis women and their Anishinaabe ancestors embroidered floral motifs onto clothing using thread, beads, or porcupine quills. Moccasins, coats, gloves, and leather bags were thus adorned with white, yellow, blue, purple, and red embellishments. This remarkable craftsmanship earned the Métis a lasting legacy as the “flower beadwork people,” a testament to their skill and cultural expression.

Among them was Catherine Lacerte. Catherine beaded and embroidered wildflowers reminiscent of the riverbanks along which her grandmother once walked. Her delicate style, however, reflected Europe, where her grandfather’s roots lay.

Born in 1843 to Métis parents, Catherine learned beadwork as a child and was later taught embroidery techniques when she attended schools run by French-Canadian nuns.

Prairie Flowers near Broadview, Assiniboia.Edward Roper, watercolour and gouache over pencil on laid wove paper, 1887. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1989-446-31.

Prairie Flowers near Broadview, Assiniboia.Edward Roper, watercolour and gouache over pencil on laid wove paper, 1887. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1989-446-31.

Lovely prairie anemones, white sagebrush, big bluestem and muhly grasses once bloomed along the riverbanks of what was then known as the Red River Settlement.

Inspired by these wildflowers, Métis women and their Anishinaabe ancestors embroidered floral motifs onto clothing using thread, beads, or porcupine quills. Moccasins, coats, gloves, and leather bags were thus adorned with white, yellow, blue, purple, and red embellishments. This remarkable craftsmanship earned the Métis a lasting legacy as the “flower beadwork people,” a testament to their skill and cultural expression.

Among them was Catherine Lacerte. Catherine beaded and embroidered wildflowers reminiscent of the riverbanks along which her grandmother once walked. Her delicate style, however, reflected Europe, where her grandfather’s roots lay.

Born in 1843 to Métis parents, Catherine learned beadwork as a child and was later taught embroidery techniques when she attended schools run by French-Canadian nuns.

In 1862, Catherine, who by then had become the first Métis teacher in the Red River Settlement, married Joseph Mulaire, a fur trader from Yamaska (Quebec).

It is almost a given that when Joseph arrived in the Red River Settlement, he wore a saencheur flechey or ceinture fléchée — an arrowed, woven sash, inspired by Indigenous braiding techniques and French-Canadian tradition. By the late 1700s, the sash was standard issue to all voyageurs, along with a blanket, wool stockings and pants.

Made of sheep’s wool, the sash served many practical purposes: it fastened coats, was used as a harness during long days of canoeing and portaging, and helped support heavy loads. It was voyageurs from Lower Canada who brought them to the West. Until around 1850, sashes were generally all red. Later, the colourful Coventry sashes appeared and it became more the norm than the exception.

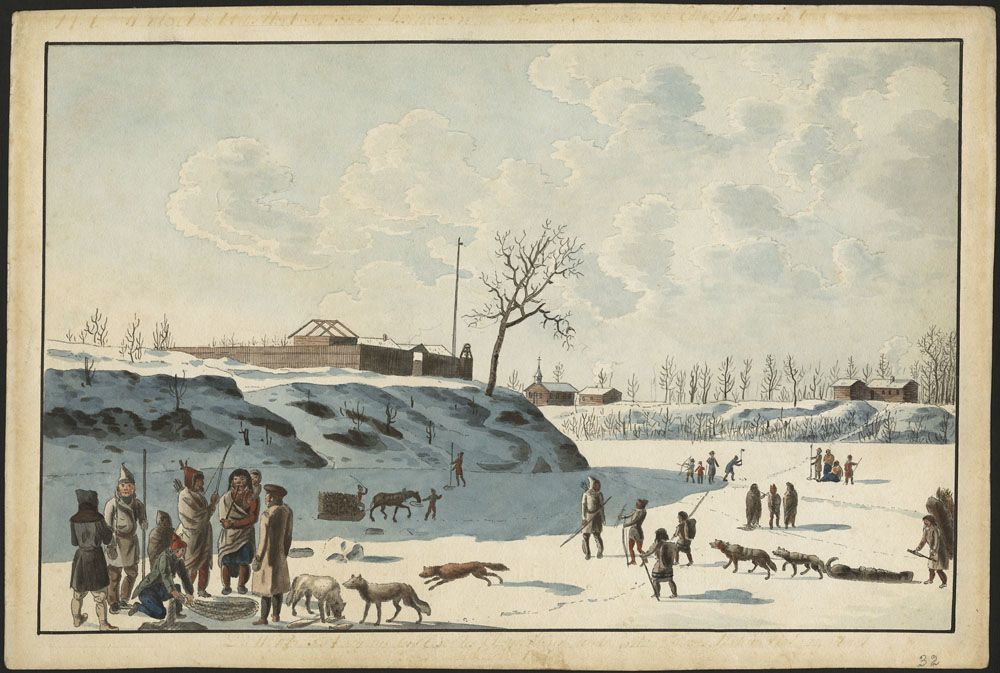

Winter fishing on ice of Assynoibain & Red River. Peter Rindisbacher, watercolour on paper, 1821, Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1988-250-31

Winter fishing on ice of Assynoibain & Red River. Peter Rindisbacher, watercolour on paper, 1821, Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1988-250-31

Winter fishing on ice of Assynoibain & Red River. Peter Rindisbacher, watercolour on paper, 1821, Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1988-250-31

Winter fishing on ice of Assynoibain & Red River. Peter Rindisbacher, watercolour on paper, 1821, Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1988-250-31

In 1862, Catherine, who by then had become the first Métis teacher in the Red River Settlement, married Joseph Mulaire, a fur trader from Yamaska (Quebec).

It is almost a given that when Joseph arrived in the Red River Settlement, he wore a saencheur flechey or ceinture fléchée — an arrowed, woven sash, inspired by Indigenous braiding techniques and French-Canadian tradition. By the late 1700s, the sash was standard issue to all voyageurs, along with a blanket, wool stockings and pants.

Made of sheep’s wool, the sash served many practical purposes: it fastened coats, was used as a harness during long days of canoeing and portaging, and helped support heavy loads. It was voyageurs from Lower Canada who brought them to the West. Until around 1850, sashes were generally all red. Later, the colourful Coventry sashes appeared and it became more the norm than the exception.

It is here that our historical story merges with the contemporary. Where the legacy of Catherine Mulaire and the history of the sash come together in the work of two current Manitoba fashion entrepreneurs, Andréanne Dandeneau and Miguel Vielfaure.

From Catherine to Anne: The Making of Anne Mulaire

When Andréanne (Anne) Mulaire Dandeneau launched her clothing collection 20 years ago, she wanted it to reflect who she was. As she was searching for inspiration, her father showed her a delicate embroidery piece created by her ancestor, Catherine Mulaire.

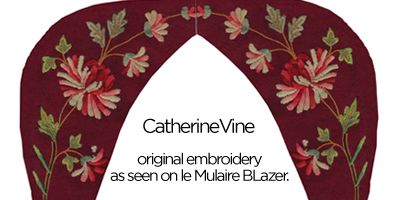

"She had embroidered this incredibly beautiful vine. When I saw it, I thought, ‘This is my brand.’ It’s in my blood; it’s where I come from," Andréanne said.

This floral motif — created from “flowers she found near the Seine River," a tributary of the Red River in Manitoba — became known as "Catherine’s Vine" in Anne Mulaire designs.

Except for her father, the artist behind some of the floral designs that adorn Anne Mulaire's clothing, Andréanne has assembled an all-female team in her workshop, which is located just a stone's throw from the Red River.

"In my 20-year career, I’ve had to fight, I’ve had to say, ‘I’m worth something,’" she says, explaining how she quickly noticed the overwhelming presence of men in the world of design.

As a result, she made it a priority to hire women who wanted to build careers in fashion and train them for roles traditionally held by men—such as fabric cutting, for example.

"I’m proud to tell the world that we’re an all-women team."

Leaning on Indigenous values, the Anne Mulaire brand supports a circular fashion economy to divert fabric from ending up in landfills and ethical employment standards. Threads are sourced from India, Pakistan, or Turkey, and transformed into textiles in Canada, where hiring age, working conditions, and wages are regulated.

“I’m very eco-conscious, very proud to be a female entrepreneur, and very proud to be Métis. All of it is interconnected,” she said.

“It’s made in Canada, it’s environmental, it’s Métis. Those three things are me.”

From Sash to Sensation: The Making of Étchiboy

Around the same time that Andréanne started creating her designs, Miguel Vielfaure was working as an interpretive guide at Winnipeg’s Festival du Voyageur. He wore a historical costume which was authentic "except for the sash,” he said. “Which was made of polyester."

Miguel started looking for a sash made the old-fashioned way, on a loom out of wool, but it just wasn’t available.

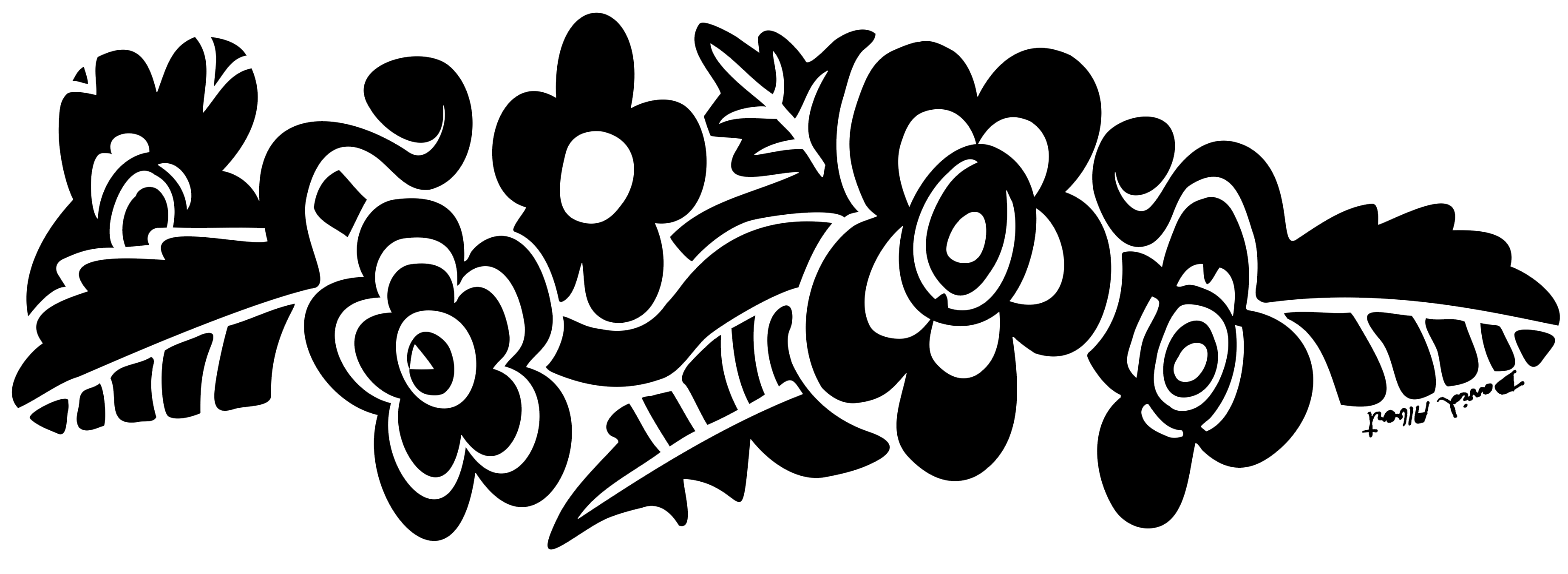

Then on a trip to Chinchero near Cusco, Peru, he met people who were weaving on a loom. Their patterns reminded him of arrowed sashes. From his desire to own an authentic saincheur flechey and that encounter with this Indigenous weaving group, Étchiboy was born.

The word Étchiboy means "Eh, little boy" in Michif, one of the languages of the Métis.

Miguel partnered with a collective of Quechua weavers to produce sashes the way they would have been made back in the 1800s.

The collective supports single mothers and families in Peru through sustainable employment as all the wool is produced, dyed and woven there. In addition to weaving sashes, the collective is now making other items. Like the Métis, they embroider flowers on handbags and ankle boots.

Cultural and social responsibility is important to Miguel.

“There are much easier ways to make money,” he admits. “If you want to make money while helping people, you face more challenges — but also more rewards.”

The riverbanks have changed a great deal since the days of Andréanne and Miguel’s foremothers but new generations of Métis continue to proudly display and carry forward the legacy of their ancestors.

A Métis Guide to Winnipeg

⇓

The Forks

Photo: Travel Manitoba

Photo: Travel Manitoba

The Forks, where the Assiniboine and Red Rivers meet, is the birthplace of Winnipeg and a must-visit destination, according to Miguel Vielfaure and Andréanne Dandeneau.

For millennia, it was a meeting place for the Anishinaabe, Cree, Dakota, and Nakoda peoples. In 1738, Pierre Gauthier, Sieur de La Vérendrye, established the first trading post there.

It was also where families were formed from the unions of Canadian voyageurs and Indigenous peoples. Later, it became the Red River Settlement, part of Hudson’s Bay Company territory, and later a key transit point for trains bringing immigrants.

Today, The Forks is alive with a market, local shops, and museums. From there, the Esplanade Riel leads to Saint-Boniface.

“It’s beautiful. There’s always something new happening there,” says Andréanne Dandeneau.

“It’s a way to experience history,” adds Miguel Vielfaure.

In winter, visitors can even skate on the river’s frozen surface.

Canadian Museum for Human Rights

CANADIAN MUSEUM FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, photo by Ian McCausland

CANADIAN MUSEUM FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, photo by Ian McCausland

A visit to Winnipeg isn’t complete without seeing the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Located at The Forks, the museum stands as a striking landmark on Winnipeg’s skyline.

One section of the museum is dedicated to the Métis.

“There’s so much history, and it’s done really well,” notes Andréanne Dandeneau.

However, Miguel Vielfaure warns, “It’s really well done, but it’s about injustices. It’s still a bit depressing.”

The museum offers a profound and thought-provoking exploration of human rights struggles and triumphs, making it a must-see for anyone visiting Winnipeg.

Manitoba Museum and Saint-Boniface Museum

Manitoba Museum. Photo: Travel Manitoba

Manitoba Museum. Photo: Travel Manitoba

For Miguel Vielfaure, the Manitoba Museum is a gem that tells the story of Manitoba, from prehistory to the present. A significant section is dedicated to the Hudson’s Bay Company, featuring a centrepiece: a replica of the Nonsuch ship.

“It’s the history of Manitoba, which includes Métis history, from the time when the Métis were in charge to when the government destroyed entire villages,” he explains.

To delve deeper into Métis history, Louis Riel, and the Francophone heritage of Saint-Boniface, he also recommends visiting the Saint-Boniface Museum.

Museum St. Boniface. Photo: Tourism Winnipeg

Museum St. Boniface. Photo: Tourism Winnipeg

Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG)

Photo: Salvador Maniquiz /Tourism Winnipeg

Photo: Salvador Maniquiz /Tourism Winnipeg

Andréanne Dandeneau has a soft spot for the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

“They always have something new; it’s fun,” she says. “They bring in artists from elsewhere, and Winnipeg artists also create installations. They showcase art and fashion—it’s amazing.”

Andréanne Joly

Andréanne Joly loves to explore, delve into, and showcase the francophone culture of Canada and its attractions. She has been doing so for 20 years and would continue to do it for 100 extra years as the richness, beauty, and diversity of Canada's destinations amaze her. As a journalist and writer, she collaborates with NorddelOntario.ca, Culinary Tourism Alliance, Francopresse.ca, L'Express.ca, and more.

Embrace Canada with Landsby

Landsby creates unique and immersive experiences that not only provide travellers with purposeful and enriching trips but aim to positively impact the communities being explored.