From Gold Rush to Gourmet

Yukon’s Enduring Sourdough Tradition

From Gold Rush to Gourmet

Yukon’s Enduring Sourdough Tradition

Inside Chef Cat McInroy’s fridge in her home in Whitehorse is a living piece of Yukon history.

It is just a small jar of unassuming beige paste, but it represents the resilience of generations of Yukoners. “I’m extremely protective of it,” Cat says. “It’s a piece of the Yukon. It belongs to everyone and to no one.”

The “it” is a sourdough starter that traces its ancestry to the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898. If handled with care, this living culture will outlast every person who touches it.

Cat grew up in Whitehorse, the youngest of seven, in a family where the kitchen was the centre of life. She spent time out on the land and on the trapline, learning what it takes to survive in the North.

She went on to join the RCMP, but always loved food and cooked in her spare time. When she retired from the force, Cat went back to school, eventually earning a Red Seal certification in both cooking and pastry and opening up her own cooking school in Whitehorse — the Well Bread Culinary Centre.

It was through this venture that Cat connected with Ione Christensen, a trailblazing Yukoner whose great-grandfather crossed the Chilkoot Pass in the winter of 1897–98 on his way to Dawson City in search of gold. Although the exact story is lost to history, it is likely that somewhere on that long trail , another miner handed over a spoonful of starter.

"This was really common in that time for people to share sourdough starter," Cat said. For prospective gold miners, who were required to carry 1,000 pounds of food over the pass, the starter was a source of life, much lighter than carrying leavening agents such as baking soda.

Miners kept the starter in little leather medicine pouches close to their bodies as they moved. And they continued to use it even after arriving in Dawson.

"It's not like there was a big pipeline up here of getting groceries," Cat said. "So, sourdough starter was the thing that kept the miners and their families alive".

Ione's family passed the starter down from generation to generation for more than a century. It was tradition for the women in the family to be the caretakers of the starter and, having no female descendants to pass it down to, lone chose Cat to carry on the legacy.

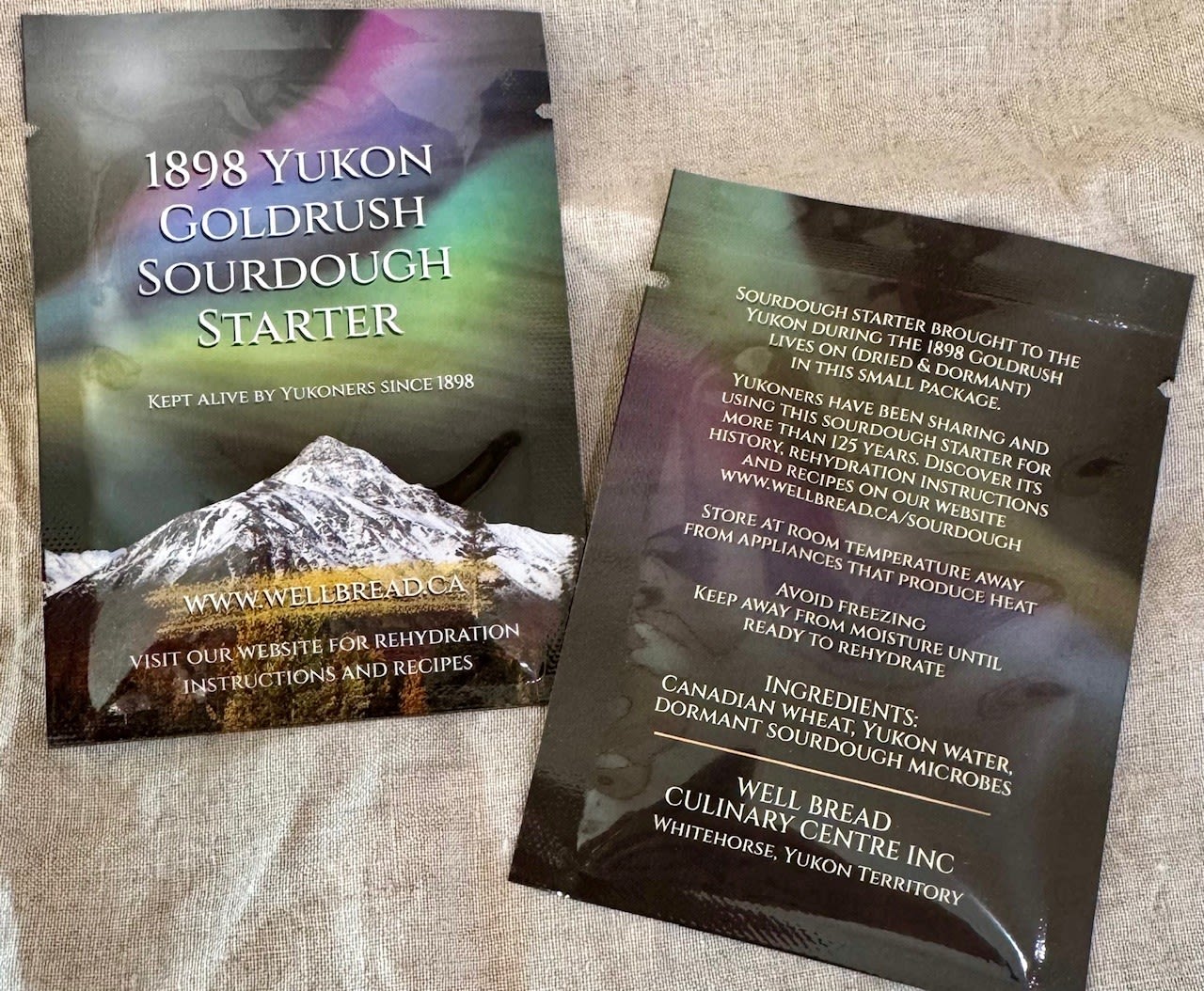

People can order a piece of that 1898 starter from the Well Bread Culinary Centre to make their own bread.

"I've shipped this all over the world," Cat says. "It has gone to every continent, and that includes Antarctica."

Sourdough starter is a simple mixture of flour and water animated by wild yeast and bacteria from the air. Unlike commercial yeast, a single strain, a starter is a thriving microbiome.

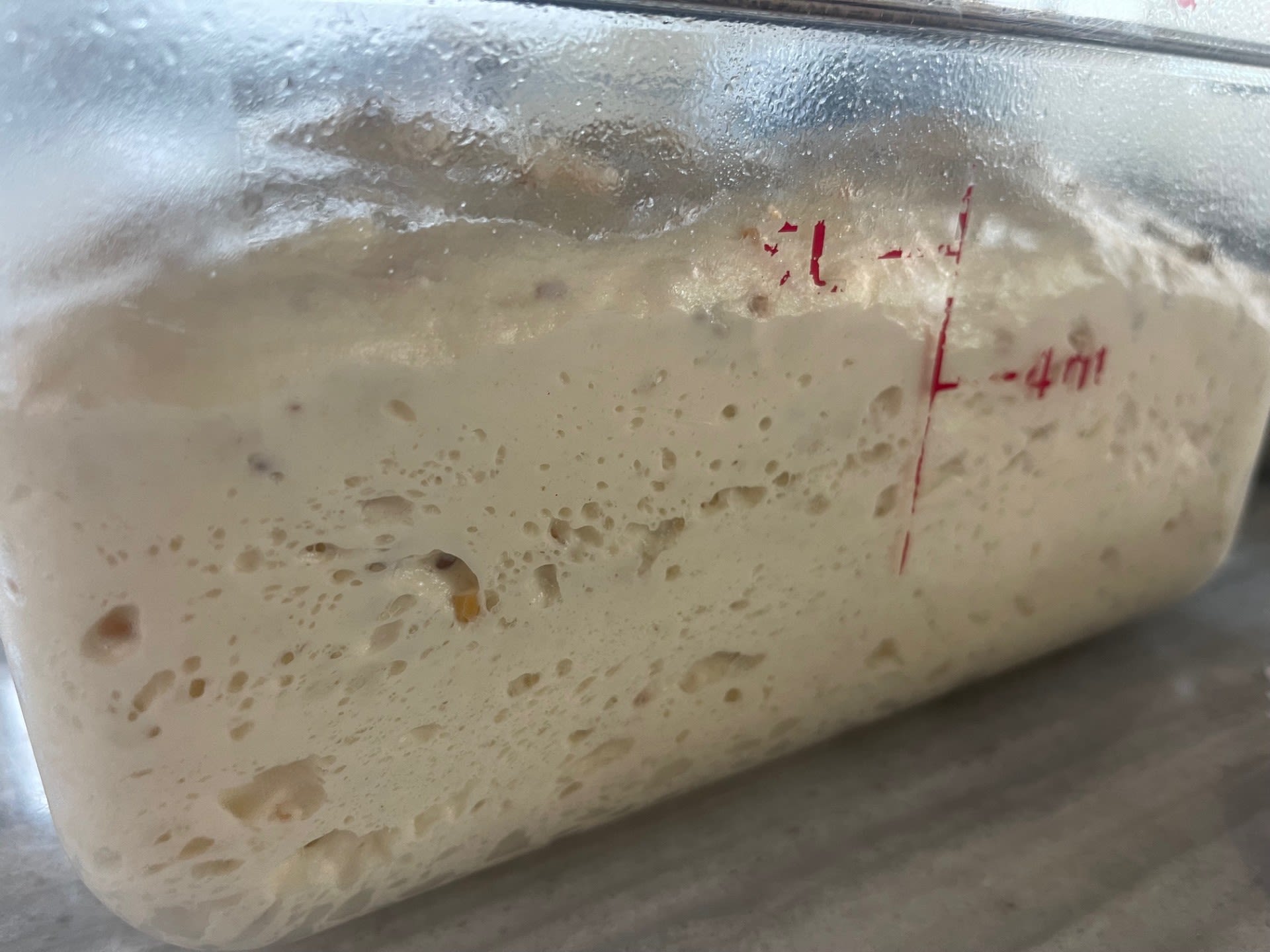

"Once that microbiome is healthy and active, it blooms," Cat explains.

When she wants to use the starter for bread, she removes it from the fridge, where it lives in a semi-dormant state. Cat warms it to room temperature and feeds it flour, water, and a pinch of white sugar because “this Yukon starter loves a bit of sugar,” she laughs. Within eight to ten hours, it’s frothing and ready.

She takes a half cup or so and puts it back in the fridge, ready to activate for another day. The rest becomes bread, cinnamon buns, or whatever she’s making or teaching that week.

"It is like having a pet," she says. "And you do have to care for a pet if you want to keep it alive."

In the Yukon, the word sourdough became synonymous with the hardened life of the north. Surviving a full northern winter earned newcomers the nickname: you had proved you could endure, just like the starter itself. “If you survived a winter here, you were a sourdough,” Cat says.

Yukon sourdough, while holding a big part in the territory's history, taps into an ancient story. In Egypt, archaeologists have uncovered 4,500-year-old bread vessels whose tiny cracks still held dormant wild yeast and lactic-acid bacteria. Researchers were able to reactivate the starter and bake bread from it, proof that the same invisible microbes that lifted Cat’s dough in the Yukon once leavened bread along the Nile.

The Yukon starter has even found a home half a world away. A few years ago, scientists from the Puratos Sourdough Library in St. Vith, Belgium — an archive dedicated to preserving wild yeast cultures from every corner of the globe — took a sample of the 1898 starter.

DNA testing showed the same microbial makeup as San Francisco’s famed sourdough, backing the long-held belief that miners carried a bit of California north during the Gold Rush. Today that Yukon culture rests in a climate-controlled vault as “starter number 106.”

Cat’s voice softens when she speaks of the future.

“I want this thing to live on. I want Ione Christensen and her family’s legacy to live on,” she says. For her, the jar in the fridge isn’t a business; it’s a trust. “I don’t make money off this. I have a piece of Yukon history and I’m passionate about carrying it forward.”

When the time comes to hand it off, she already knows what matters: “I’ll find someone with the same integrity I have, someone who will keep it from being commercialized. I don’t ever want to see this thing in a store.”

A hundred and twenty-seven years after miners shared a spoonful of living dough on the Chilkoot Trail, the culture still passes from hand to hand. In Cat’s care, and in the care of whoever comes next, Yukon’s sourdough will keep rising.

Step into Canada's Golden Hour