The Lake Remembers: Fishing, Culture, and the Tłı̨chǫ Way

Long known for trophy-sized fishing, Lac La Martre Adventures begins to tell a deeper story

From 6,500 feet in the air, the land below looks endless: rock, dark forest, and scattered pockets of water stretching out in all directions. I’m flying north from Yellowknife by floatplane, the twin otter skimming above the terrain, heading toward Clemy Island on Lac La Martre in the Northwest Territories.

From this height, I can make out a single ribbon of road as it cuts through the landscape, a pale thread leading toward Whatì, the only overland connection between this Tłı̨chǫ community and the territorial capital of Yellowknife.

Beyond the road, Lac La Martre appears, the third largest lake in the Northwest Territories.

Mike, our pilot from Air Tindi, adjusts course slightly as we bank over the water, the floatplane angling toward Clemy Island, where our destination, the Lac La Martre Adventures fishing lodge, sits.

For decades, the lodge was only partially owned by the Tłı̨chǫ First Nation. Now, the lodge is fully under Tłı̨chǫ ownership and management. It’s a shift that goes beyond logistics — it marks a meaningful change in who gets to tell the story of this place.

The Lodge at the Centre of It All

Lac La Martre Adventures is only accessible by floatplane or boat. There are no roads to Clemy Island, and the nearest community — Whatì — is across the large lake. When you arrive, you’re stepping into a place that’s remote by design.

Guests are met at the dock and helped to one of nine cabins, which are simple, comfortable, and spaced out along the island’s shoreline. The main lodge serves as the dining and gathering area, where meals are skillfully prepared daily by Debbie Porter, whose homestyle cooking is quickly becoming part of the lodge’s draw.

Fishing is the reason people come to this remote corner of Canada. The lake is known for its northern pike and lake trout, touting some of the largest in the world. It’s not unusual for guests to catch and release dozens in a single day. The water is shallow and weedy in places, ideal territory for big fish.

The pace is relaxed, and mornings start early. Guides meet you at the dock. They pack a lunch or plan for a shore lunch of fresh fish, and then head out for the day. In the evenings, everyone gathers for dinner. Afterwards, some people congregate in the lodge, others sit by the fire outside and take in the view.

I arrive in early August, when the sky finally begins to darken at night. On clear evenings, a faint ribbon of green sometimes shimmers low on the horizon — a preview of the Northern Lights that become more vivid later in the month and are a staple of the night sky from September to April. over media

A Cultural Layer

The lodge is still, first and foremost, a fishing destination. That hasn’t changed. But with the Tłı̨chǫ First Nation now fully owning and managing the operation, there’s an effort underway to include more cultural experiences alongside the angling.

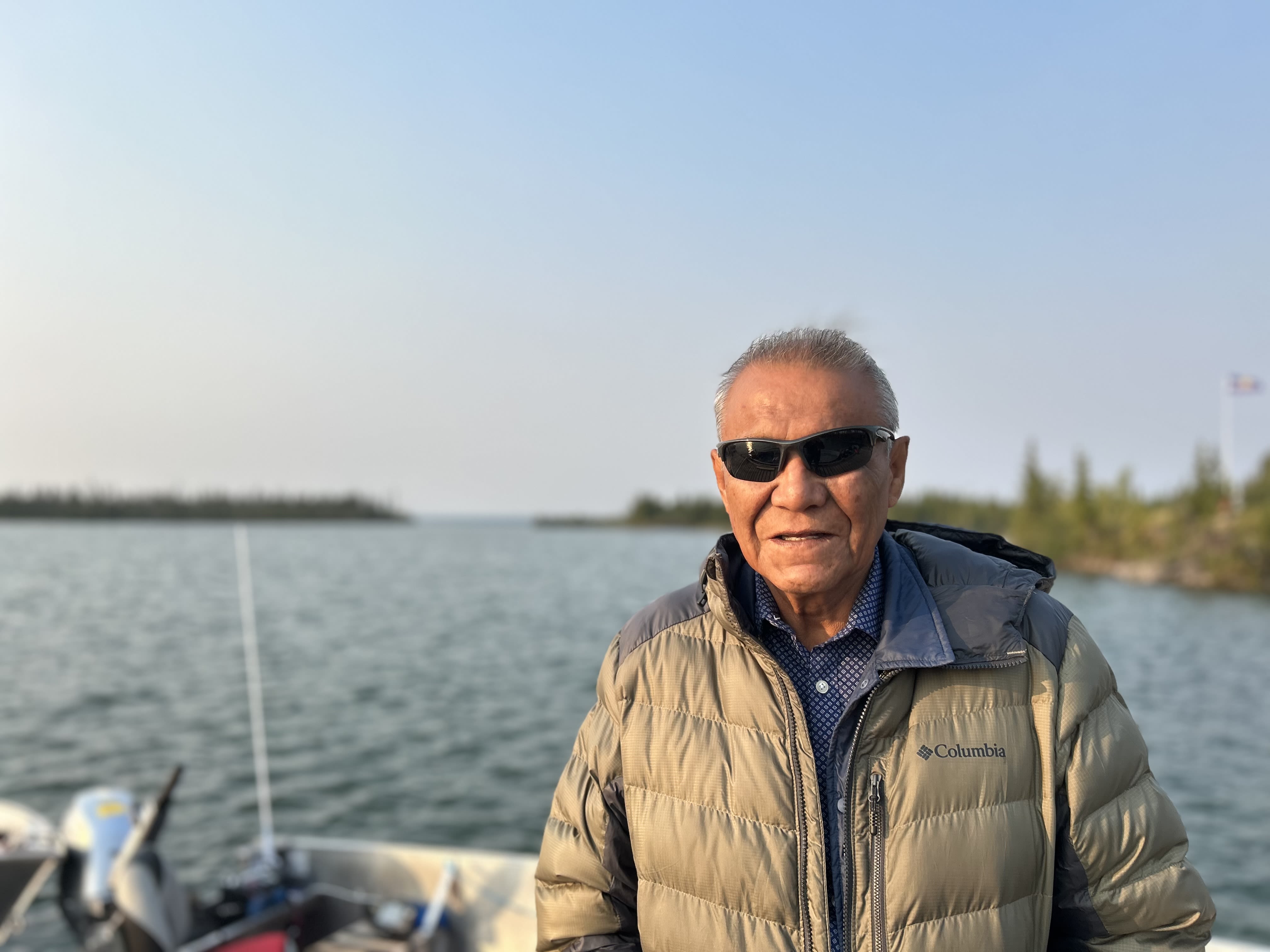

Shortly after my arrival, I sit down with Elder Michel Moosenose. He lives in Whatì and has come out to the lodge to visit and share stories. We talked in the dining room as staff prepared our next meal in the adjoining kitchen.

Elder Michel Moosenose

Elder Michel Moosenose

Michel is quiet and introspective, but excited to tell me the stories of his people and this place.

We chat about his childhood, growing up by this vast lake. He tells me about travelling across it in winter with his father, moving by dogsled over the ice. They would set traps for rabbits and hunt caribou, spending days at a time on the land.

I asked what it was like in the darkness of winter, when daylight is brief and the cold settles in. He looked out across the lake for a moment, then said, “We had the northern lights to light our path. It was almost as bright as daylight.”

Creating meaningful employment opportunities for Tłı̨chǫ citizens is one of the aims of the lodge, says Samantha Stuart, the Director of Tourism for Tłı̨chǫ Adventures Ltd (the organization that operates the lodge).

"An Elder-in-Residence program that would bring community leaders like Michel to the lodge to speak with guests is one of the ways we are considering layering in Tłı̨chǫ culture into the offerings at the lodge," she says. Other ways include training Tłı̨chǫ citizens as fishing guides, creating opportunities to showcase important cultural sights around the lake through guided tours and hikes.

On Lac La Martre, the lines cast into the water go deeper than expected: You come for the fishing. You leave with a clearer sense of place.

Later that afternoon, Michel joins fellow Tłı̨chǫ staff members John Tinqui and Johnboy Simpson to set a traditional fishing net in the water. The net hasn't been used for some time, and it takes a while to get it detangled and ready. They are assisted by Zack Brown, the Operations Manager, who has been working at the lodge for 15 years.

As I watch them patiently work together, I can't help but think this is a symbol of the way forward: cooperation, curiosity and respect.

There was no formal program or presentation — just a chance to join in or observe as the trio sets the net and, the next morning, returns to harvest the catch.

That seems to be the approach here. If guests are curious, they’re welcome to participate. If not, they can keep to the usual routine of guided fishing and lodge downtime. The goal, according to those I spoke with, is to offer a fuller picture of life on the lake so visitors can begin to understand the land through the people who know it best, and so the community can revitalize culture through tourism.

Johnboy Simpson provides guided fishing at Lac La Martre Adventures

Johnboy Simpson provides guided fishing at Lac La Martre Adventures

The changes are subtle. A guest might be invited to hear a story around the fire, or learn what it once meant to cross the lake by dogsled in winter, long before floatplanes brought visitors in from Yellowknife. These aren’t performances, they’re parts of a living culture, shared on its terms.

On Lac La Martre, the lines cast into the water go deeper than expected: You come for the fishing. You leave with a clearer sense of place.

Canada. Crafted by Canadians.